“Back to Normal” Runs on Workers from the Global South

D.W. McLachlan reviews the history of how capital pilfers labour from the Global South in times of crisis to propose a new theory of change that centres those workers and their communities.

Our economy is a mouth that eats healthcare workers to keep restaurants running.

Socialists will control COVID-19 outbreaks and spread by preventing the extraction of essential professionals and workers from the Imperial Periphery, also known as the “Global South”[1]. We will do this by directly supporting organizers in the Periphery so they can resist Core attempts to displace them. We will also reduce the “demand” for Peripheral workers in the Core through direct mitigation and education in leftist spaces and workplaces. By blocking the “supply” of healthcare workers from the Imperial Periphery, we will force the state to protect healthcare workers in the Core. Since healthcare workers are not an isolated population, this requires comprehensive and effective public health measures. This theory of change has broad historical precedent.

A theory of change is a generalized, living plan for how to achieve the ends of a movement. As COVID runs rampant through our leftist spaces and comrades, we must do something to resist. Change can be achieved by focusing on internationalism, organizing toward socialist objectives in workplaces and communities, and directly providing COVID mitigations and education. Our enemies already embrace internationalism, fueling social murder inside workplaces and communities through the exploitation of immigrants, particularly healthcare workers.

Before unpacking a potential theory of change, some history and theory are in order. The existing theories of change in leftist spaces depend either on mass mobilizing, advocacy, or direct action. Here is an interesting theory of change from BDS (Boycott, Divest, and Sanction), the movement to promote Palestinian liberation by targeting the zionist entity oppressing them.

"BDS aims to end international support for Israeli violations of international law by forcing companies, institutions and governments to change their policies. As Israeli companies and institutions become isolated, Israel will find it more difficult to oppress Palestinians[2]."

This is an economic and material theory of change which identifies the organization, its ultimate goal, and the strategies that will influence the material, economic factors required to achieve that goal. In the schema I propose above, this is a theory that combines mass mobilizing and direct action through a boycott, and advocacy through sanctioning and divestment. Good theories of change also suggest a plausible mechanism by which change will be achieved, in this case by inflicting economic damage. BDS is an organization and Israel (i.e. “the zionist entity”) is a clear target. The relationship between the group, target and strategy is clear. Further, it has historical cachet: a BDS campaign played a significant role in the success of the movement against South African Apartheid[3]. This is a good theory of change!

"We Shall Return" by Imad abu Shtayyah

Here is another theory of change that would match popular sentiments around electric cars as a force to achieve environmental justice:

"Consumers will achieve environmental justice by purchasing electric vehicles (EVs) rather than vehicles powered by internal combustion engines (ICEs). As fewer ICE vehicles are built, less fuel will be burned and less carbon will be emitted, achieving environmental justice."

The problems with this theory of change are extensive. “Consumers” are not an organized group that can achieve anything but selecting from a narrow range of consumption options in a market, by definition. Environmental justice is not limited to “greening” any product or category or even reducing emissions. Actual justice requires at least some reconciliation with the logic or system that maintains the injustice. Buying a different personal vehicle reinforces the logic of the system that got us here. Finally, the strategy depends on a demonstrably false assumption: less fuel does not, in fact, get burned as renewables and electrification get integrated into the grid; the new capacity instead gets used for more production and more profit[4], to say nothing of the monstrous emissions required for the manufacture of EV batteries. This theory also erases the lives and communities of people in the global South where the environmental burden of the extraction of precious materials mostly takes place. This theory of change is self-defeating, and I would argue that since it centers “consumers” instead of any intentional group people may form, that is the point.

In arriving at the theory of change I propose, I have spent over a year studying the history of internationalism and its theorizing under Marxism-Leninism. The historical parallels between COVID-19 as a force of slow death and abandonment are very clear. The first historical example comes from yellow fever in New Orleans in the 19th century. Dr. Kathryn Olivarius, a historian at Stanford University, has provided an outstanding history of this period and the social forces at work in society at the time[5]. Yellow fever is a very dangerous insect-borne disease that killed about 50% of the people who contracted it in the 19th century. It was active every few summers in New Orleans until the frost killed off the mosquitos in fall. However, unlike COVID-19, a yellow fever infection confers lifelong sterilizing immunity–you can only get yellow fever once, one way or another. The massive death toll, where up to 10% of the city’s population was killed every summer of an epidemic, led to interesting interventions from the capitalists in the Cotton Kingdom at the time.

In New Orleans, the logic of slavery fueled a great deal of the suffering in unexpected ways. For the white ruling class, enslaved Black people were a form of capital; an enslaved person is a means of production. As a preview of our current #DavosSafe paradigm of public health for me but not for thee[6], slave owners spread the myth that Black people couldn’t catch yellow fever while they carefully and self-consciously protected the enslaved people they owned from the disease. To continue production while protecting the enslaved, immigrant populations were used as disposable labor. Much like the present moment, simultaneous crises (famine and political instability) guaranteed this supply and millions of Irish, German and other European working-class people were removed from their homes to the United States. Tens of thousands ended up in New Orleans and thousands died of yellow fever. To quote Olivarius,

"In 1835, British writer Tyrone Power rode out to the swamp to see the Irishmen digging the canal and asked a foreman why he was not using enslaved Black labor for such a difficult task. Power was told that enslaved people could not “be substituted to any extent; a good slave costs at this time two hundred pounds sterling, and to have a thousand such swept off a line of canal in one season would call for prompt consideration.”[7]"

The attempted isolation of enslaved Black people did not prevent their deaths, even though these were rarely counted as deaths from yellow fever due to the slave owners’ myths. As an organizer, I learn this history on the edge of my seat: This is happening again! How can we organize the workers who are now being “swept off a line of canal in one season” by COVID? 150 years later, I hope that we can use this history and find the strength to resist the same myths that facilitated their murders.

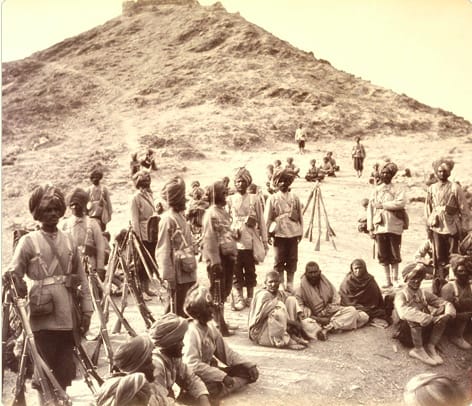

The case of New Orleans and yellow fever is only one example of how capitalism uses colonialism and imperialism to secure a supply of labor and ameliorate its contradictions. Here are two other examples. In 1842, to secure a strategic position in South Asia, Britain declared war on Afghanistan. However, the 1820s to 40s was a time of great political tension and instability in Europe (known as the “age of revolution”) and soldiers were needed to put down rebellions at home. So, to continue securing markets and resources, colonized populations were used. Nearly 4 000 Indian sepoys (a sepoy is a locally recruited infantry soldier from colonized India), plus an unknown number of Indian “camp followers” from a total group of 12 000 were deployed to fight the disastrous First Anglo-Afghan War[8]. This is the same technique that France used to secure its empire when soldiers from the entire so-called “French Union” were deployed in colonial and imperial projects. Consider Algeria, for example: In WWI alone, 250 000 Algerian colonized soldiers were made to fight for France. These same colonized peoples were used to police French colonies in Southeast Asia to put down the Viet Minh independence movement of the Indochinese Communist Party starting in 1935. This is an extremely common pattern in imperialism. Labor is one of the key resources extracted from a colony, whether it be enslaved people, soldiers, or healthcare workers.

Canal Digging in NOLA by Irish Immigrants courtesy of LOC. Retrieved.

Canal Digging in NOLA by Irish Immigrants courtesy of LOC. Retrieved.

As in the pandemics of the past, the ongoing COVID pandemic is causing labor shortages (or, more precisely, a smaller Reserve Army of Labor). In effect, our leaders have determined that we must feed healthcare workers and other “essential” workers to SARS-CoV-2 to support a service economy and maintain labor discipline. After these workers have been killed or maimed and can no longer work, society still needs their jobs to be done. To that effect, we are now seeing a huge pilfering of healthcare workers from the Imperial Periphery by the Core[9][10][11]. These workers are being displaced primarily from the Philippines, Mexico, and India (i.e., for 2018, see “Which Countries Do Immigrant Healthcare Workers Come From?”, which appears to be data that was made available to New American Economy Research Fund on special request. It does not seem controversial to suggest that it’s unlikely that this trend has been reversed in the years since[12]).

Turning to history once again, a path forward becomes clear. To fight Capital in Vietnam in the Viet Minh, the peace movement in France and Algeria directly targeted the deployment of soldiers to what is now Vietnam[13]. We see the same calls to action now in support of Palestinian liberation: block materiel and soldiers being mobilized to support the imperialists[14]. We can force the crisis of capitalism’s contradictions in the Imperial Core by restricting the supply of healthcare workers from the Periphery.

45th Rattray's Sikhs with prisoners from the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1857. Retrieved.

To support our comrades in the Periphery, we have to organize with them. They have needs that we must hear and use our positions of privilege, power, and wealth to help them meet. This is a call to action to identify comrades with ties to the Imperial Periphery, listen to them and organize to meet the needs of the communities they had to leave. Ultimately, we want to serve their homelands, helping their local comrades and communities to resist global capitalism where they’re strong and Capital is weakest. The healthcare workers who we displace are, in their original communities, potential supporters, revolutionaries and medics in the struggle. The resultant weakening of Capital around the world will strengthen us so we can fight for the concessions and ultimate fractures that we need to secure a good society everywhere. In the better world we make, we hope it will be possible to meet our comrades around the world in person safely.

Through an analysis of the long history of direct struggle against Capital, I bring this theory of change: Capital is weaker in the Imperial Periphery, so it is there that we must strike. We will organize with our comrades from the Periphery to keep their workers local. At the same time, we will use the thousands of Clean Air Clubs, Mask Blocs, and other COVID-conscious organizations to keep us and our communities here safe and reduce the need for stolen workers. As Capital falters amid mass debility and infection and is starved of labor by its own contradictions, we will push for change and ultimately revolution. This is how we win.

D.W. McLachlan is an activist and member of SCORE. He has been active in the climate justice and Land Back movements and now the movement for COVID action.

Notes

Throughout this article, I use the term Imperial Core to refer to what many may colloquially understand as “The West” or “The First World”. In the parlance of the Core/Periphery/Semi-Periphery terminology developed by sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein in World-systems theory, the Global South or “Third World” or “Underdeveloped Countries” are known as the Imperial Periphery. For more discussion, see: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199743292/obo-9780199743292-0272.xml ↩︎

https://www.aamarchives.org/who-was-involved/local-authorities.html ↩︎

Richard York, Shannon Elizabeth Bell, Energy transitions or additions?: Why a transition from fossil fuels requires more than the growth of renewable energy, Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 51,

2019, Pages 40-43, ISSN 2214-6296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.01.008. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629618312246) ↩︎McAllister, Olivarius Kathryn Meyer. Necropolis Disease, Power, and Capitalism in the Cotton Kingdom. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022. ↩︎

https://coviddatadispatch.com/2023/01/22/covid-source-shout-out-safety-protocols-at-davos/ ↩︎

Chapter 3, Immunocapital in Olivarius, Kathryn Meyer. Necropolis Disease, Power, and Capitalism in the Cotton Kingdom. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022. ↩︎

Pages 132-133 in Perry, J. M. (1996). Arrogant armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. Trade Paper Press. ↩︎

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/aug/14/africa-health-worker-brain-drain-acc ↩︎

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2023/06/canada-announces-new-immigration-stream-specific-to-health-workers.html ↩︎

https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migration-and-the-health-and-care-workforce/ ↩︎

https://archive.is/7BUAN originally https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/immigrant-healthcare-workers-countries-of-birth/ ↩︎

Armstrong, Elisabeth. Bury the Corpse of Colonialism: The Revolutionary Feminist Conference of 1949. University of California Press, 2023. ↩︎

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/11/7/protesters-block-us-military-ship-allegedly-carrying-weapons-for-israel ↩︎